We didn’t know much about each other twenty years ago. We were guided by our intuition; you swept me off my feet. It was snowing when we got married at the Ahwahnee. Years passed, kids came, good times, hard times, but never bad times. Our love and respect has endured and grown. We've been through so much together and here we are right back where we started 20 [sic] years ago—older, wiser—with wrinkles on our faces and hearts. We now know many of life's joys, sufferings, secrets and wonders and we're still here together. My feet have never returned to the ground.

《喬公合巹廿載與妻書》

憶昔廿秌之前,與卿相識尚淺。然靈犀一點,寸心頓通,吾似雙足騰空,陟彼虗崈。纓脫於“婀婳旎樓”【注】,時雨雪霏霏。日居月諸,養兒育女,所歷境遇重重,或順或艱,幸畧無逆者。與卿互愛互敬,此情經久彌沈。囘望來途脩遠,卿伴吾行,今乃歸訪廿載前啟程處也。唯斯人共夀,其智俱增,眉間紋皺,心頭痕深。夫娑婆諸般苦樂奇秘,盡得體之味之,朋侶一路至此,可謂偕老乎。而吾心遊化界,雙足何嘗須臾觸地哉。

【注】加州名酒店也。

A FOREWORD

By Lu Gusun

序言[1]

陸穀孫

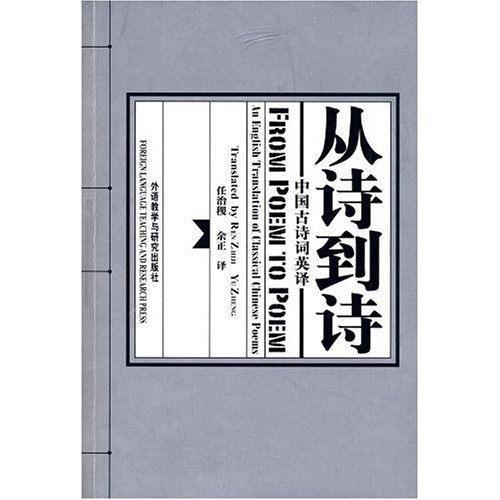

Robert Frost said, "Poetry is what gets lost in translation." Not necessarily: that thousands upon thousands of poems get translated back and forth in the world is evidence enough to the contrary. And if you, dear Reader, take a look at the poems translated below in this book, you'll find the meaning conveyed faithfully, cultural milieu kept in tact, and the poetic ethos enriched. Little, if anything, is lost.

羅伯特·弗羅斯特氏嘗言:“所謂詩意,失于移譯者也已。”僕恐未必盡然。極目宇內,詩詞譯作何啻千萬,足證斯言之確非。而讀者諸君凡經眼此卷譯詩者,即可知其絕勝之處有三:詞義忠信,風神完固,文采瞻鬱。即有所失,不亦微夫。

Nevertheless, nobody has dwelt with greater cogency upon the enormous difficulty involved in poetry translation than Frost in the above-quoted remark. As I see it, translation of poetry requires that the translator have the makings of a poet in him or her. He/She absorbs the source poems with innate poetic sensibilities until they become part of his/her aesthetic being. The empathy is such that the absorbed poems stir, agitate, even haunt him/her, making the utterance of them an absolute must as Jin Shengtan said. By now the translator has to turn to be a poet in the target language in his/her own right, relying on an abundance of prior poetic experience in it. A songster, as it were, who cannot enjoy a minute of peace of mind unless the song is sung. Poetry translation worth its salt invariably involves such a receptive-productive process.

然論譯詩之艱,弗氏此語可謂知言之極。竊以爲,譯詩人當有作詩才,得以風騷玄悟,餮納原詩,然後消之化之,融匯性靈,腹中心中,翻沸迭蕩,爲夢爲魘。其神入之深,情專之切,金聖嘆[2]所謂“必欲說出之一句話”是也。于譯入之文字,更須渤涉嵩覽,靜味細玩,方可稱詩家。一如歌人,曲不竟謳,則須臾難休。是故,必先吞隋珠,吐和璧,而詩之良譯可待矣。

Professor Ren Zhiji or Charles Jen as he is known in the US, an old friend of mine since the 1960s, from whom I've learned a lot as it was our wont to discuss matters concerning English and other subjects so much so that during the so-called Cultural Revolution in China we were accused of "scratching each other's back in a coterie like the Hungarian Petrofi Club," has enough qualifications of this kind and to spare. He was born an Odysseus, not that he seeks adventures, but that he is a nostalgic by nature. I remember swapping writings in English with him for comment or pleasure reading in the early 1960s. One sentence in one of his essays has never escaped my memory: "Suddenly a cuckoo called. The only audibility in the mountains. And we were thinking of mother."

任兄治稷教授先生,以“任查理”之名聞達于美利堅國,乃僕卌載舊雨,昔日長與暢論英文幷其餘諸事,多承惠澤教益,以至“文革”釁起,兄與僕爲肖小誣作“裴多菲俱樂部互相撓背抓癢之徒”。以其造詣精微,翻譯詩詞,固非峻業。兄生而具奧德賽之氣質,此非言有貪奇弄險之癖,實謂有懷舊追往之好。猶記四十年前,以英文酬唱,互指疵瑕,相與爲樂。兄文中有一金句,僕未嘗或忘于心間:“忽聽子規吟。山深空留音。聞者憶慈親。”

For Ren, emigration happened when he had outlived an ardent age. What remains now is no longer the ecstasy of new horizons but rather the apotheosis of memory. No wonder he has zeroed in on ancient Chinese poetry mostly with a motif of nostalgia and homesickness. People notice that unless he/she is a dolce vita in the mainstream, a feeling émigré, like Milan Kundera, cannot but look back and sing with a heart throbbing with emotion worthy of a Homeric epic: "Alone, in a sadness sublime,/And tears come!" (See page ??) Greater[Jason Chu1] pathos is couched in seemingly light-hearted lines such as "Kids.../Asked me smiling WHERE'S MY HOME" (See page ??) I feel my old friend is tackling a reconciliation with the finitude of life with these lines. In this sense, the value of Ren's translations far exceeds poetry alone but is a good sample of diasporic literature.

任兄始寓美國,已逾花酒盛年。初入异邦新域之大樂既逝,今淹留者惟冥然兀思往事而已。是以所譯詩詞,皆遴柬撫昔戀鄉之作,未足奇也。大凡游子多愁,若非佼佼然逞志于他國者,其必如米蘭·昆德拉氏,不能不回望前塵,心怦怦動,于焉萌甦之情,何其淵默,即以荷馬詩史出之,亦不爲過:“獨愴然而泪下”(見第?頁)再如“兒童……笑問客從何處來”(見第?頁)之語,乍看似戲謔,然內中自有力感頑艶之哀。竊忖兄或以此詩句,聊慰浮生有限之憾恨。以此觀之,兄之所譯,非特閾于歌詩一區,洵爲羈客文學之楷式哉。

Technically, Ren's preference to condensed, succinct phrasal utterances instead of to drawn-out, grammatically viable sentences shows how well he grasps the quintessence of poetry. Stylistic devices like synesthesia (e.g., "Green moss lit up by the echoing flare") abound only where they are comfortably apt. Rhythm and rhyming are continuously a Kierkegaard Either/Or proposition in poetry translation. Ren handles both with aplomb; unrhymed but pleasantly rhythmic lines are fully justified especially when the translator aims at an English-speaking readership accustomed to a time-honored poetic tradition traceable to Shakespeare's blank verse.

以詩藝論,任兄雅好凝煉,不拘字義文法之桎梏,不落贅詞冗句之窠臼,真知詩之三昧者。修辭藻繪,若“聯覺”之類(如“複照青苔上”之譯句),惟契合文脉處,方得見用。韵、律之于詩歌,齊格高氏[3]所謂“非此即彼,不可兼得”者。而兄犀心夢筆,無不信手拈來。英美詩學,素尊家法,究其本源,則莎士比亞之“白詩”也。兄之譯作,遣句遂少韵而多律,琅琅可誦,蓋俾英語讀者習慣便利之故耳,詎可以此非之乎。

Mr. Yu Zheng, the other translator, is but a slight acquaintance. He did excel among his age peers when he studied at Fudan University, Shanghai, in a class which both Ren and I taught. He has since been remembered as an assiduous and affable young man -- with few words but a lot of promise. If he doesn't feature prominently in this foreword, I sincerely beg his pardon.

余正老弟,襄協譯事,惜僕與其交識尚淺。曩在海上,負笈復旦,任兄與僕嘗授課業,以爲有卓越同倫之秀。因知此君,勤勉謙退,訥于虛言而敏于躬踐。拙序嘉贊未多,千祈勿罪。

-------------------------------------------------------------------------

[1]受業 文冤閣大學士 謹譯

[2]金聖嘆(1608-1661),本名采,字若采,入清後改名人瑞,字聖嘆。吳縣(今江蘇蘇州)人。于《致家伯長文昌書信》中,嘗雲:“詩非异物,只是人人心頭舌尖所萬不獲已,必欲說出之一句說話耳。”

[3]通譯“克爾愷郭爾”——譯者注

-------------------------------------------------------------------------

阿拉伯利比亚人民社会主义民众国太祖荒天漠地肇极开基饰文黩武扰外殇内哀皇帝,姓卡扎菲,讳穆阿迈尔。壬午年四月辛卯生,其先贝都因部。少习戎事,遂欲问鼎。乙酉秋,举事,兵不血刃,废伊德里斯一世。时犹未而立,不称帝,自封上校。治哲学,作绿皮书,以“伊斯兰社会主义”治国,诛伐异己。恃苏维埃联盟淫威,渐与美利坚国不睦。丙寅春,美师承熹宗里根旨,空袭京畿的黎波里,一公主死焉。戊辰冬至,美民航客机忽坠英吉利国洛克比镇。世皆谓太祖阴谋之,列邦遂绝往来,凡十年。然辛未骤变,俄罗斯一蹶不振,美国所向无匹,太祖乃萌意修好。癸未,以空难罪己,欲外通贸易。辛卯,内乱顿作,例以雄兵镇之,不息,蔓而难图。会欧美盟军夹攻,致六龙西狩,潜入虞渊,运筹抵御,抗衡一时。以敌众倍,终不支。三子先后见执。九月丁未,遇流寇,遭射杀。传崩前疾呼曰:“央视误我,召忠误我!” 论曰:太祖少年枭雄,驰骋大漠。不忘家法,恪守圣训。好居氊庐,常墨镜持枪,谈笑从容。御林红巾翠袖,萦绕左右。其享国也,挟地利以集富,凭外援而称豪。然夜郎独夫,心益骄固,安能久守此势。一旦失倚,自诩偏安,则卌载霸业,黄粱立熟,其幻如蜃楼矣。

RSS Feed

RSS Feed